Ledger 2: ‘General Thomas Morgan and Jane Morgan

Thomas Morgan, (1702–1769), was the son of John Morgan and Martha Vaughan and younger brother of Sir William Morgan. On his father’s death in 1719, Thomas, as the second son, inherited the Rhiwperra estate while William inherited the Tredegar estate.

On 24th May 1723, at the age of just 21, Thomas was elected Member of Parliament for Brecon, a seat he held until 1734. Thomas then represented Monmouthshire 1734-1747 and Breconshire from 1747 until he died in 1769. For just 6 weeks short of 46 years, Thomas served as M.P. for the three seats controlled by the Morgans for generations. During his time in the House of Commons, he voted with successive Whig Governments (1721-1762), led by such notables as Sir Robert Walpole; Spencer Compton, 1st Earl of Wilmington; Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle and William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire.

Given the dominance of land-owning classes in Government, it is no surprise that Thomas voted in favour of Walpole’s Excise Bill in March 1733. Walpole’s bill would further the interests of the landed country gentlemen who were his supporters, by reducing the rate of land tax from 4 shillings in the pound to just 1 shilling. The bill also included a provision to address the problem of mass smuggling by replacing the import duty on tobacco and wine with an excise tax payable by all consumers.

This was a deeply unpopular move, coming on the back of Walpole’s 1732 unkind reinstatement of the salt tax for three years, with all the proceeds granted to the royal family. It was only two years earlier that the tax had been repealed due to the hardship inflicted on ordinary people and its effect on agriculture and trades such as leather and glass that used salt during manufacture. There was

massive opposition to the 1733 Bill, from the population and particularly from the London merchants. The protests nearly brought down the government, and the measure was swiftly dropped on 9th April.

On 18th June 1731, Thomas succeeded his brother, Sir William Morgan, as Lord Lieutenant and Custos Rotulorum of Brecknockshire and Monmouthshire, offices he held until his death; he was also appointed brigadier-general of the militia of those counties.

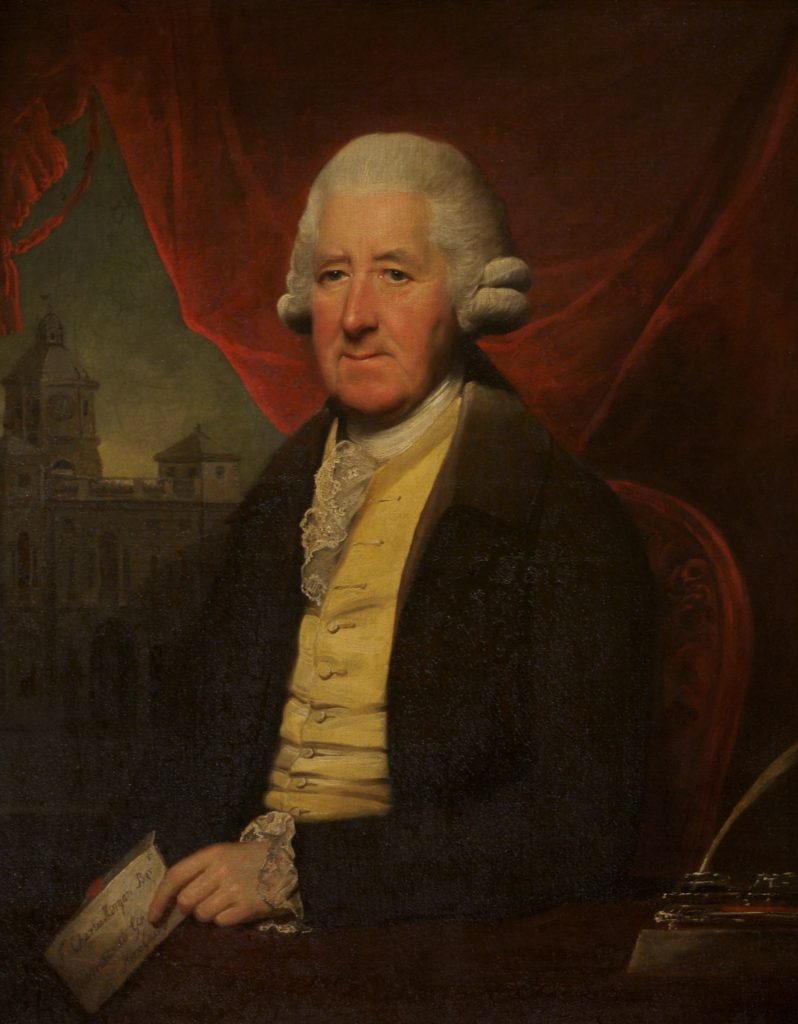

Thomas Morgan was a respected lawyer and in 1741 he was appointed Judge Advocate General, responsible for the court-martial process within the Royal Navy and British Army. In this office, he became known in Monmouthshire as “General Morgan” though he did not hold any military rank in the King’s forces. The Newcastle Courant announced his appointment as “The King has been pleased ….to grant to Thomas Morgan Esq the Office of Advocate General, or Judge Martial of all his Majesty’s Forces both Horse and Foot raised or to be raised for his Majesty’s Service within England, Wales and the Town of Berwick upon Tweed.” In 1768, He resigned from this office and was succeeded by his deputy and son-in-law, Charles Gould (pictured below).

In 1726, Thomas married Jane, the second daughter and co-heir of Col. Maynard Colchester M.P. & Jane Colchester (nee Clarke) of Westbury Court, Gloucestershire. They had five children: Thomas (b.1727), Jane (b.1731), Katherine (b.1735), Charles (b.1736), and John (b.1742). All three sons failed to provide Jane with any grandchildren.

On 26th October 1754, Jane’s uncle Sir Thomas Clarke, Bart. died without issue leaving her his estate at Brickendonbury, Hertfordshire, which the Derby Mercury reported as “We hear by the Death of Sir Thomas Clarke, Bart. That the Hon. Thomas Morgan of Ruperra in Glamorganshire, Esq. comes in for the Hertfordshire Estate and all the Personal, which is very considerable.” The Morgans built extensions to the manor and laid out a fine avenue of trees that links the mansion to Hertford. To this day it is known as the “Morgan Walk”.

Thomas and Jane were able to spend their time between their estates at Brickendonbury, Rhiwperra in Glamorganshire and Dderw in Brecknockshire. When his nephew, Sir William Morgan died intestate in 1763, Thomas, the nearest male relative, inherited the Tredegar Estate in Monmouthshire, thus holding substantial estates in four counties.

Thomas appears to have taken charge of Tredegar immediately and set about resolving the many problems that came with the agricultural estate. It was not until 1766 that he embarked on a programme of works to improve the external structure and internal fabric of the mansion.

Since the death of Sir William in 1731, the estate had been poorly managed with shortfalls in income; for example in 1745 the Settled Estate should have brought in £5,616.4s.4¾d, but only

£4,320.3s.11½d was ever paid. This can almost certainly be attributed to William Morgan inheriting the estate at the age of just 6, and who suffered poor health throughout his life and probably had little interest in involving himself in estate matters. 7

While Thomas was working to improve matters at this substantial estate, his succession rights were contested by his niece Elizabeth and her husband William Jones, even though Sir William’s will is clear that the estate would revert to Thomas, should his male heirs die without issue. Elizabeth Jones asserted that her brother had intended for her to inherit the estate. She also disputed his right to the furnishings in the house and had many valuable items removed into storage at a ‘malthouse’ in Bassaleg. She effectively held them to ransom by threatening to sell them unless Thomas bought them back, though it is not clear if Thomas did that, or whether she sold them to someone else. However, at least some items were certainly returned to Tredegar.

There must have been a great deal of family tension between Thomas Morgan, Elizabeth and his sister-in-law, Rachel. She had not received the £2000 per annum payable by the estate under her marriage settlement, though Thomas appears to have been able to resume payments in 1767. 8

Elizabeth’s case came before the Lord High Chancellor in Lincoln’s Inn Court on Friday 15th December 1769 but by this time Thomas had died and his son, also Thomas had inherited the estate and became a party to the case. However, the fate of so great a property was too much for this court, and the case was referred to the judges of the King’s Bench. The Jones’ claim to Tredegar was finally thrown out in 1774 (after both Thomas’s father and son had died and Charles Morgan had taken the ownership of Tredegar). However, they continued to fight for the arrears of Lady Rachel’s income and disputed the ownership of other estate lands until 1793.9

Thomas Morgan died at Horse guards, Whitehall on 12th April 1769 aged 66 after suffering a lingering illness (Chester Courant 18th April 1769), his wife Jane having died in 1767 died aged 64.

The Tredegar Estate Records at the National Library of Wales include details of the expenses incurred on Thomas Morgan’s lavish funeral –

“a hearse, six black horses and two coaches for 10 days, eight men on horseback ‘to attend the journey’ for 10 days as well as ‘expenses on the road. ….. the innermost coffin of three was lined with ‘fine white silk’ and the ‘very strong outside Elm Coffin’ with four pairs of ‘burnished contrast’ handles was covered with a rich black velvet trimmed with the best brass nails”

His Will also at the National Library of Wales shows he died a wealthy man, leaving Brickendonbury Rhiwperra and Tredegar to his family. To his children, he left large sums of money and bequests-

“….to my dear Son, John Morgan all such sums of money more or less that is in my purses or otherwise in a strongbox in the iron Chest in my House at Rhiwperra except that … in my Dowry purse and the Jewels which will belong to my dear son Thomas Morgan and I also give to my said Dear Son John Morgan the little picture of myself which my wife had and which I promised him some time ago and also the picture of my said dear son Thomas Morgan. I likewise give my said Son John Morgan my gold repeating watch”.

He also left his wife, Jane Colchester, his “best Coach and my post Chaise with the harness and appurtenances and six of my best Coach horses to be chosen by her. I also give to her the use of all my jewels and my plate for her Life”

Sadly Jane had died in 1767 so these items were left to her children.

It is quite surprising that the wealthy Thomas and Jane are not commemorated with large and expensive marble memorials as we see for their predecessors. Their graves are simply marked with black ledger slabs of polishable crystalline limestone. The ledger for Thomas has a circular low relief carved shield to the head comprising Morgan, Meredith ap Bleddyn, Bleddri ap Cadifor Fawr and Llwch Llawen Fawr arms with Colchester arms in pretence, while Jane’s is …..

However, two large hatchments in the nave commemorate their lives.